This is the sixth section of Chase’s 2023 Reading in Review, a series of posts where Chase reflects on books read in 2023. The first is here. The reviews don’t assume you have read the works, and don’t spoil their experiences. This section primarily discusses:

East of Eden by John Steinbeck

How to Behave in a Crowd by Camille Bordas

How to Pronounce Knife by Souvankham Thammavongsa

Out There by Kate Folk

The Dangers of Smoking in Bed by Mariana Enriquez

Full list of works discussed here.

This post goes over a few other things I read in 2023 that are worth commenting on, mostly about vulnerable children in strange scenarios.

I read for the first time John Steinbeck's East of Eden and loved it. The introduction to Adam Trask as a child is a great concise piece of characterization. Adam's family feels tense and dangerous. We see this in the kind of violent, dangerous details (again, O'Connor and Moshfegh's capabilities): Adam's father Cyrus is not just a womanizer and a drunk, we learn:

He contracted a particularly virulent dose of the clap from a Negro girl who whistled at him from under a pile of lumber and charged him ten cents. When he had his new leg, and painfully knew his condition, he hobbled about for days, looking for the girl. He told his bunkmates what he was going to do when he found her. He planned to cut off her ears and her nose with his pocketknife and get his money back. Carving on his wooden leg, he showed his friends how he would cut her. “When I finish her she’ll be a funny-looking bitch,” he said. “I’ll make her so a drunk Indian won’t take out after her.” His light of love must have sensed his intentions, for he never found her. By the time Cyrus was released from the hospital and the army, his gonorrhea was dried up. When he got home to Connecticut there remained only enough of it for his wife.

This is a threat to the narrative, an ugly unreleased tension that holds tight as we consider the young Adam. It boils into his relationship with his brother Charles, with whom Adam is competitive and there is additional violence and tension.

It starts to twist with the story of how Cyrus develops. The mean, bad soldier stumbles into a leadership position in the military. Steinbeck tells it as a farce, as we know Cyrus is no brilliant military mind or great character, but he twists it more. By getting praised and discussed as a leader, Cyrus begins to show leadership qualities. By the end of his life, he's a changed man, he speaks with intelligence, wisdom, consideration, and the development seems so precarious, so lucky that the mean "devil" Cyrus has the chance to become learned. It reflects back on the world, says something larger: gee, how fragile all things are and how tender it is that he got to become someone meaningful and not just a total loser.

What Steinbeck does so well after this is all about subversion. He would be adept at telling a "mean little life" story for Adam, something like a Roald Dahl childhood or like what Eileen undergoes in Moshfegh's novel. But everything gets twisted, the world looks so dark that it's shocking when any kind of tender life gets shown.

Steinbeck twists the relationship more between Adam and Cyrus, his father. We get a comparison of Adam and his brother Charles, we know that Charles is the son of Cyrus's current wife while Adam's mom is dead, Charles is more athletic, Charles is more outgoing. We expect Adam's life to be a bit cruel. We are told in vivid detail a fact of Adam's sensitivity is that he hides in the woods. He holes up in a tiny literal hole in the ground to feel a sense of void and loneliness (this is a beautiful image and section, shocking to find it here, it's the kind of thing I don't associate with Steinbeck). We also learn Adam's biggest fear: "As Adam grew he feared one thing more than any other. He feared the day he would be taken and enlisted in the army. His father never let him forget that such a time would come. He spoke of it often. It was Adam who needed the army to make a man of him. Charles was pretty near a man already. And Charles was a man, and a dangerous man, even at fifteen, and when Adam was sixteen."

The twist comes as Cyrus takes Adam on a walk in the woods. It goes in the direction we expect, and more: not only is Cyrus too assertive to Adam, he raises the stakes, insists that gentle Adam will join the army. Cyrus describes the violence that will come to Adam if he refuses. But then the twist, Adam tells Cyrus about his big secret practice:

As they walked back toward the house Cyrus turned left and entered the woodlot among the trees, and it was dusk. Suddenly Adam said, “You see that stump there, sir? I used to hide between the roots on the far side. After you punished me I used to hide there, and sometimes I went there just because I felt bad.

“Let’s go and see the place,” his father said. Adam led him to it, and Cyrus looked down at the nestlike hole between the roots. “I knew about it long ago,” he said. “Once when you were gone a long time I thought you must have such a place, and I found it because I felt the kind of place you would need. See how the earth is tamped and the little grass is torn? And while you sat in there you stripped little pieces of bark to shreds. I knew it was the place when I came upon it.”

Adam was staring at his father in wonder. “You never came here looking for me,” he said.

“No,” Cyrus replied. “I wouldn’t do that. You can drive a human too far. I wouldn’t do that. Always you must leave a man one escape before death. Remember that! I knew, I guess, how hard I was pressing you. I didn’t want to push you over the edge.”

It's sensitive and tender, strange for a man we have been shown is mean and spiteful and who was just threatening Adam. They continue to walk and Adam brings up his brother. What happens, slowly, well paced, is more strange and tender than we expect.

But Adam said, “Why don’t you talk to my brother? Charles will be going. He’ll be good at it, much better than I am.”

“Charles won’t be going,” Cyrus said. “There’d be no point in it.”

“But he would be a better soldier.”

“Only outside on his skin,” said Cyrus. “Not inside, Charles is not afraid so he could never learn anything about courage. He does not know anything outside himself so he could never gain the things I’ve tried to explain to you. To put him in an army would be to let loose things which in Charles must be chained down, not let loose. I would not dare to let him go.”

Adam complained, “You never punished him, you let him live his life, you praised him, you did not haze him, and now you let him stay out of the army.” He stopped, frightened at what he had said, afraid of the rage or the contempt or the violence his words might let loose.

His father did not reply. He walked on out of the woodlot, and his head hung down so that his chin rested on his chest, and the rise and fall of his hip when his wooden leg struck the ground was monotonous. The wooden leg made a side semicircle to get ahead when its turn came.

It was completely dark by now, and the golden light of the lamps shone out from the open kitchen door. Alice came to the doorway and peered out, looking for them, and then she heard the uneven footsteps approaching and went back to the kitchen.

Cyrus walked to the kitchen stoop before he stopped and raised his head. “Where are you?” he asked.

“Here—right behind you—right here.”

“You asked a question. I guess I’ll have to answer. Maybe it’s good and maybe it’s bad to answer it. You’re not clever. You don’t know what you want. You have no proper fierceness. You let other people walk over you. Sometimes I think you’re a weakling who will never amount to a dog turd. Does that answer your question? I love you better. I always have. This may be a bad thing to tell you, but it’s true. I love you better. Else why would I have given myself the trouble of hurting you? Now shut your mouth and go to your supper. I’ll talk to you tomorrow night. My leg aches.”

It's mean as it is loving in the same breath. This is a great scene, an inversion of Kafka's “The Judgement”, and Steinbeck capitalizes off its momentum. It's a great enactment of Baxter's principle for subtext: give a character something amazing that he doesn't want. Adam doesn't want to be the apple of his father's eye, he wants the safety from his violence. This is the tension going into the next scene, when we are full of the dread of the fact that Adam has trumped his brother Charles in this horrible way, and his brother follows Adam out into the woods for a walk. It's like he knows the scene we just saw, we are full of dread for what might happen.

Charles moved close to him. “What did he say to you this afternoon? I saw you walking together. What did he say?”

“He just talked about the army—like always.”

“Didn’t look like that to me,” Charles said suspiciously. “I saw him leaning close, talking the way he talks to men—not telling, talking.”

Charles is not as sophisticated as Adam. He speaks and reveals himself. Rather than coyly question and prod Adam for the answer, he spills his fears:

“Look at his birthday!” Charles shouted. “I took six bits and I bought him a knife made in Germany—three blades and a corkscrew, pearl-handled. Where’s that knife? Do you ever see him use it? Did he give it to you? I never even saw him hone it. Have you got that knife in your pocket? What did he do with it? ‘Thanks,’ he said, like that. And that’s the last I heard of a pearl-handled German knife that cost six bits.” [...] “What did you do on his birthday? You think I didn’t see? Did you spend six bits or even four bits? You brought him a mongrel pup you picked up in the woodlot. You laughed like a fool and said it would make a good bird dog. That dog sleeps in his room. He plays with it while he’s reading. He’s got it all trained. And where’s the knife? ‘Thanks,’ he said, just Thanks.’ ” Charles spoke in a whisper, and his shoulders dropped.

Charles beats Adam, and it’s a terrible and rich milestone in the saga we’ve been following. The dynamic of these three men (and the woman, Alice, Charles’s mother, who factors in here greatly too) is so claustrophobic. At moments, Cyrus is Adam’s greatest ally and at moments, he’s the force to be reckoned with. Same with Charles, same with Alice. It’s a great, tense dynamic.

Steinbeck keeps developing it. As the boys get older, he broadens the setting. In an amazing section I’ve re-read many times this year, Adam goes on an odyssey through the country, switching between being in the army and being a bum. Steinbeck has settled us into a new status quo: Alice is dead, Charles is running the farm, Cyrus has moved to do military matters in the capital. The feeling of space makes the section so different than their little family house in the woods. In this journey, both Charles and Cyrus are kind to Adam, but Adam wanders and avoids them and rejects their tenderness, not just because that’s what the plot requires, but because he carries the scars of their previous life together. It’s rich and understandable psychology, painted vividly with great descriptions of big expansive America. The letter Charles writes Adam are some of the best writing I read all year. Charles’s voice is so expressive. He speaks beyond what he intends to say, and underneath his discussions of farm matters is a great terrible loneliness. He keeps talking about the knife he gave Cyrus, the one he brings up to Adam in the woods. Cyrus in Washington counsels Adam.

All this is a prologue to the events of the story, which feature a great villainous woman (misogynistically written, even if a great character nonetheless) and which asks if the experience of Adam’s childhood will happen again to Adam’s own kids. Steinbeck does a perfect clockwork job of setting up dominos in early acts and then doing nothing but knocking them down in the second half: it’s, like Andrew Martin says of Wellness, maybe too clean (I suspect Nathan Hill is a fan of this novel, they have some echoes). It’s great writing, and I’m still captivated by the exploratory early section where it feels like anything could happen.

I read two books that feature great child POV characters, both starting with the phrase “How To”. The first is Camille Bordas’s novel How to Behave in a Crowd, in which French pre-teen Isidore is managing to live his life with his large family after the death of his father. It’s a great funny story rich with deep specific POV from Isidore, who is neurotic and sensitive and prone to overthinking long deep considerations about tiny things (for example, at age 11, every time he gets a new anything, he goes and updates his will to account for who should get it if he dies. I believe he updates it based on small moment-to-moment conversations he has with his family, changing whether they deserve big or small things). The first half features Isidore attempting to run away multiple times, each time finding another non-serious excuse to return home:

The third time I tried running away, there were no good-byes—I left a note. Just a couple of miles from home, though, I realized I’d forgotten my helmet and turned the bike around to get it. The whole way back, I felt vulnerable to injury. If I died in an accident, my mother would begin a road safety campaign in my name, I thought. I made it home all right, of course, but was too tired by then to attempt leaving again. I tore up the note I’d left on Simone’s nightstand and fell asleep in my clothes.

Other good comedy comes from an overly sentimental video that Isidore watches in school about poor children who have never been to the beach, and his teacher urges them to donate money to these poor kids so they can see the beach. Isidore has a great internal debate about whether “seeing the beach” is the kind of thing that is so important that we should be contributing money to it, but ultimately gives in a lot of money. Later, he meets someone who was an actor in the video, and he’s completely floored that the video was staged. It’s a funny development.

My favorite section has Isidore totally stumped by the question of what he should be when he grows up. The scene is funny in its minute examination of his thought process, much like Baker’s Mezzanine:

Sometimes at dinner, after Simone or one of the others had given a lecture on how they envisioned their future, he’d ask what it was I planned to do in life. It made me nervous when he asked. I’d mumble something about not being quite sure yet. I thought I only had one shot at the answer, that coming up with the wrong one could loom over the rest of my life.

I tried to get serious about coming up with a vocation, for the next time he put the question to me. At the school library, I went through a guidebook that listed all the professions in existence. It actually said “all the professions” on the cover, but then there was a warning on the back, in small print, that said new professions were invented on a regular basis and that others disappeared, but that the reader should nevertheless rest assured the ones listed in the booklet should at least have a good twenty years of existence ahead. The list was four years old already. It bore 443 items, I counted, in alphabetical order. I tried to guess which ones would expire. Cartography sounded like a doomed business. Anthropology did too. I thought places and groups of people only existed in a limited number, and that once you’d studied a particular land and mapped it, or spent some time with a tribe and written about it, there was nothing to add, you’d done the job and crossed something off the list of places to map and people to study, and that the list had to be extremely short by now, if there was anything left on it at all.

Each professional title appeared in italics and was followed by a brief description of what it entailed, what kind of education you needed, how many years. I imagined the longest descriptions had to be for the most impressive jobs, and I skipped them.

I wanted to come up with something conceivable, not too showy, something my siblings wouldn’t right away try to discourage me from pursuing. On the other hand, too modest a pick would expose me to their mockery. They despised salesmen and politicians, as well as anything too useful (like plumbing, for instance) or concerned with precious things (flowers, jewelry, stationery, babies).

I thought I would read the whole booklet and find a vocation in one sitting, but by D I got bored and headed home. I didn’t see the rush in making a decision anymore. I was still pretty young. I could wait for the booklet with the new professions to come out.

The comedy here reminds me of Elif Batuman’s Selin in the best way (e.g., the very funny scene in The Idiot where Selin debates with her film professor about heads, portraits, and coins, or where Selin listens to a student at a cafe order iced tea).

There’s more pathos in the story than just comedy, and I think the grief for Isidore’s father that slowly comes out through his funny obsessions with running away, his future, his relationship with his sisters and girls, is quite well done.

The other great child POV book is Souvankham Thammavongsa’s How to Pronounce Knife, which features a number of great stories from kids’ perspectives. A favorite is “Chick-A-Chee!” in which a girl is left at home all day with her brother when her dad works. There’s a great literary wrinkle in this story which is that while the dad’s dilemma is sympathetic (the dad is a hard working immigrant, loving, and his job is precarious and he needs to ensure he keeps it), he still gives the girl an axe to protect herself with, which is the kind of ridiculous detail that makes a reader’s ears perk up.

Like Bordas, Thammavongsa marries comedy and seriousness. In one scene, the father and kids are home when someone is at their door screaming that they've got a knife.

Dad whispered that he had been thinking of opening the door but changed his mind after the man said he had a knife. “That’s no way to ask anyone for help!” Dad laughed and slapped his knee, and my brother and I laughed too, but quietly, so that the man on the other side of the door wouldn’t hear us.

The next morning, as we left for school, I noticed there was a smear of blood on our door.

The tension between the way the father handles things and the reservations of the children is resolved in a cute way. The title comes from the way he instructs his children to answer when they go knocking on doors during Halloween: you yell "Chick-A-Chee!" The kids have opportunity to correct this, to advance past their father and say "Trick or treat" instead, but they don't, they stay in their father's world. It's cute.

I enjoyed Kate Folk's collation Out There which were imaginative, mature stories ranging from speculative to just eerie.

The jacket compares it to Black Mirror, which the Silicon Valley-y opening story "Out There" definitely evokes, where "bots" identical to attractive human men have flooded the dating scene in order to steal data from single women. Folk is funny and the concept is good: I know the type of San Francisco tech guy she is satirizing, who does mindlessly and without insight recommend Haruki Murakami and go out to Big Sur. It was fun and shocking to have the premise return in a later story with a totally less satirical and more emotional tone. Stories like "Doe Eyes" and "Turkey Rumble" have the kind of violent twist that feel from Twilight Zone.

My favorite stories in Folk's collection were weirder. She has a run of great stories about strange houses, the best of which is a man who must keep the walls of a house moist with a skincare routine, and who slowly falls into an uncomfortable deep relationship with the place.

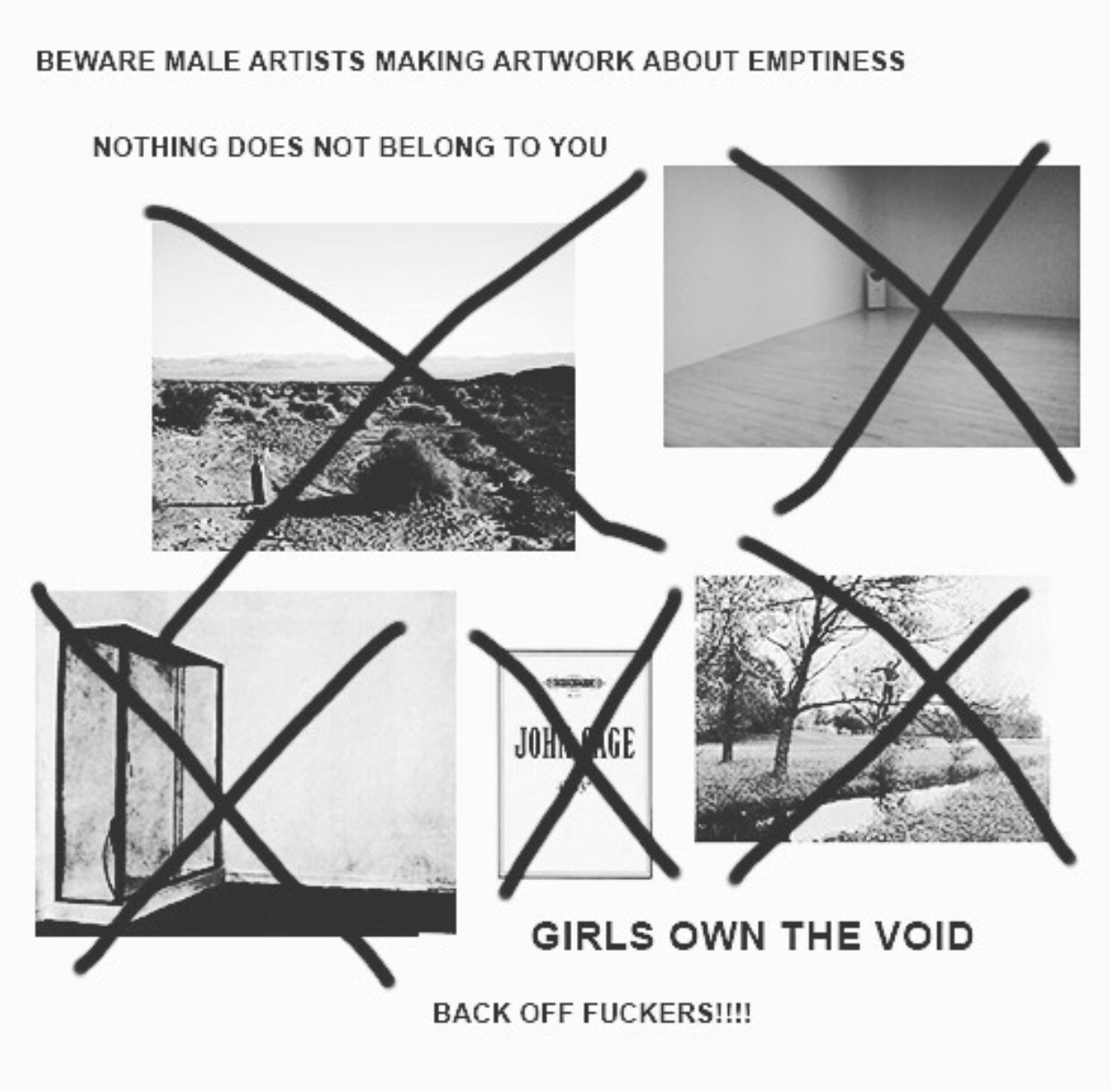

My two specific favorites were "Void Wife" and "Shelter." Both feature women who are with men who aren't quite satisfying them emotionally: I was thinking of A Touch of Jen by Beth Morgan which I love, or the genuine modern classic You Too Can Have A Body Like Mine by Alexandra Kleeman (a favorite). "Void Wife" has a great terrible premise of the world being blipped out by an encroaching void, and while the fatalism and apocalypse story of our protagonist going on her journey to live the final moments of her life are already great (and they remind of the fatalism of something like Junji Ito's “Amigara Fault”), it's the little details that make the story excellent: the way she hides in a cruise ship bath tub, such a specific idea.

"Shelter" has a narrator who Folk imbues with deep unexplained compulsive desire: she's repeatedly seeking to sleep with the men who visit her house, and she has a thanatos-y wish to be sealed into a "shelter" which would certainly kill her. That shelter, which is a concrete vault in the basement of a house she is borrowing, is an amazing thing to keep in a story. It points to Folk's interest in the sealed, hidden, subtextual dimensions of domesticity (e.g., her houses keep having weird problems), and it's a great plot point, because she keeps having to visit it and reflect on its place in the home. When one day she finds it locked and suspects someone has intruded and camped inside, it's genuinely creepy, the best "horror" moment in anything I read this year. The ending is dark and strange, the kind of thing I can see countless people in workshop saying "makes no sense" which they would be totally wrong about!

Mariana Enriquez's collection The Dangers of Smoking in Bed was similarly eerie and interesting. She's got a focus on death and ghosts/entitizes returning from death, maybe best explored in the long story to the end "Kids Who Come Back." In that story, you're spending enough time with the protagonist that Enriquez has to angle her so that she's relatable and "on your side," but there are great stories in this collection where (like Folk's "Shelter") there is much more distance between what you're thinking and what the protagonist is.

The best maybe is "Our Lady of the Quarry" in which the first-person plural narrators (what fun!) are completely contemptuous of an older, less conventionally-looks-perfect woman who is sleeping with their crush. These girls narrating discuss their own beliefs about their perfect beauty and bodies and just cannot stand that this other, older woman has their man's attention. The hatred in their voice is great, and it builds into a creepy story about swimming in a forbidden quarry. The appearance of the "lady" and the description of her is so creepy and a great development, so that it builds and twists the dynamic we had understood so far.

Another favorite is the last story, "Back When We Talked to the Dead" which also features a group of young girls as the focus. The story is about them using a Ouija board, and I liked Enriquez's "slippers on clerks" logistics of whose house they went to, where they got it, what the different socioeconomic positions of the girls were that resulted in their homes being better or worse places for them to use it. I also loved the tight POV: because our narrator believes in the Ouija board's truth, no one ever in the scope of the story has a single moment of disbelief or distrust that the Ouija board is doing anything other than contact the dead. This is great tone at work, keeping our skepticism separate from the diegesis of the story.

Click here for the seventh post of 2023 Reading in Review when it’s posted and subscribe below to get email alerts for new posts. Full list of works discussed here.