This is the seventh and penultimate section of Chase’s 2023 Reading in Review, a series of posts where Chase reflects on books read in 2023. The first is here. The reviews don’t assume you have read the works, and don’t spoil their experiences. This section primarily discusses:

Gabrielle Zevin's Tomorrow, Tomorrow, Tomorrow

Emma Cline’s The Guest

Cornelius Vanderbilt’s Farewell to Fifth Avenue

Hila Blum’s How to Love Your Daughter

Marian Engel’s Bear

Jonathan Lethem’s The Disappointment Artist

Eliza Clark’s Penance

Dorothy B. Hughes’s The Expendable Man

Full list of works discussed here.

A book I read at the start of the year was Gabrielle Zevin's Tomorrow, Tomorrow, Tomorrow, which is being celebrated and which I expect will one day be a great show for someone like HBO. I think the celebration is worth it: I enjoyed the read, even if I had some questions. I like reading about video games, and I'm a big fan of the biography about the two men who made Doom: David Kushner’s Masters of Doom. It's clear Zevin is pulling from it for her story about two friends who make video games together.

The highlights are clear: the video games they create together are interesting. I like all of the experimental games Sadie makes in college and the bigger projects they get to as they become serious industry players. Not only are their premises interesting in themselves, but I get why a story about two video game producers would have so much juice: you get the kunstlerroman creative story, the business story about industry and money and capital, the descriptions of the games themselves, and the fact that you're discussing a medium of creativity that I think most people still haven't learned to take seriously. This leads to some of the big creative moments that I imagine were exciting for Zevin to write, like the obvious one that takes place entirely in a game world.

Part of why Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow stayed on my mind all year was because of the things I didn't like about it. Both big issues, even after thinking all year, are still hard for me to articulate. The first is its safeness. Despite being life long creative partners, Sam and Sadie never seem to actually do anything terrible. Look at Cyrus and Adam in East of Eden, who share deep tender moments and horrible violent ones. Look at Flannery O’Connor. The Sam and Sadie relationship never crosses anything close to an emotional boundary, and even Sadie's iffy age-gap relationship with her teacher never feels anything other than sanitary. The stakes of the story, which should feel huge, instead feel small. The second is that even if it's clear that every element could have a place in the story, it doesn't end up connecting in a meaningful way. I'm thinking mostly about Sam's leg and injury, which never coalesces as anything, even as metaphor. A lot happens (e.g., Sadie's relationship to Sam when they first meet, a lie, a betrayl) but it doesn't feel connected or important. I think the opening could have been rearranged, we should have a sense of them as matched, great, productive creative partners: why Sam and Sadie are fated to greatness together. Instead, it's lukewarm, so that later when the relationship has bumps, they feel expected instead of tone-changing.

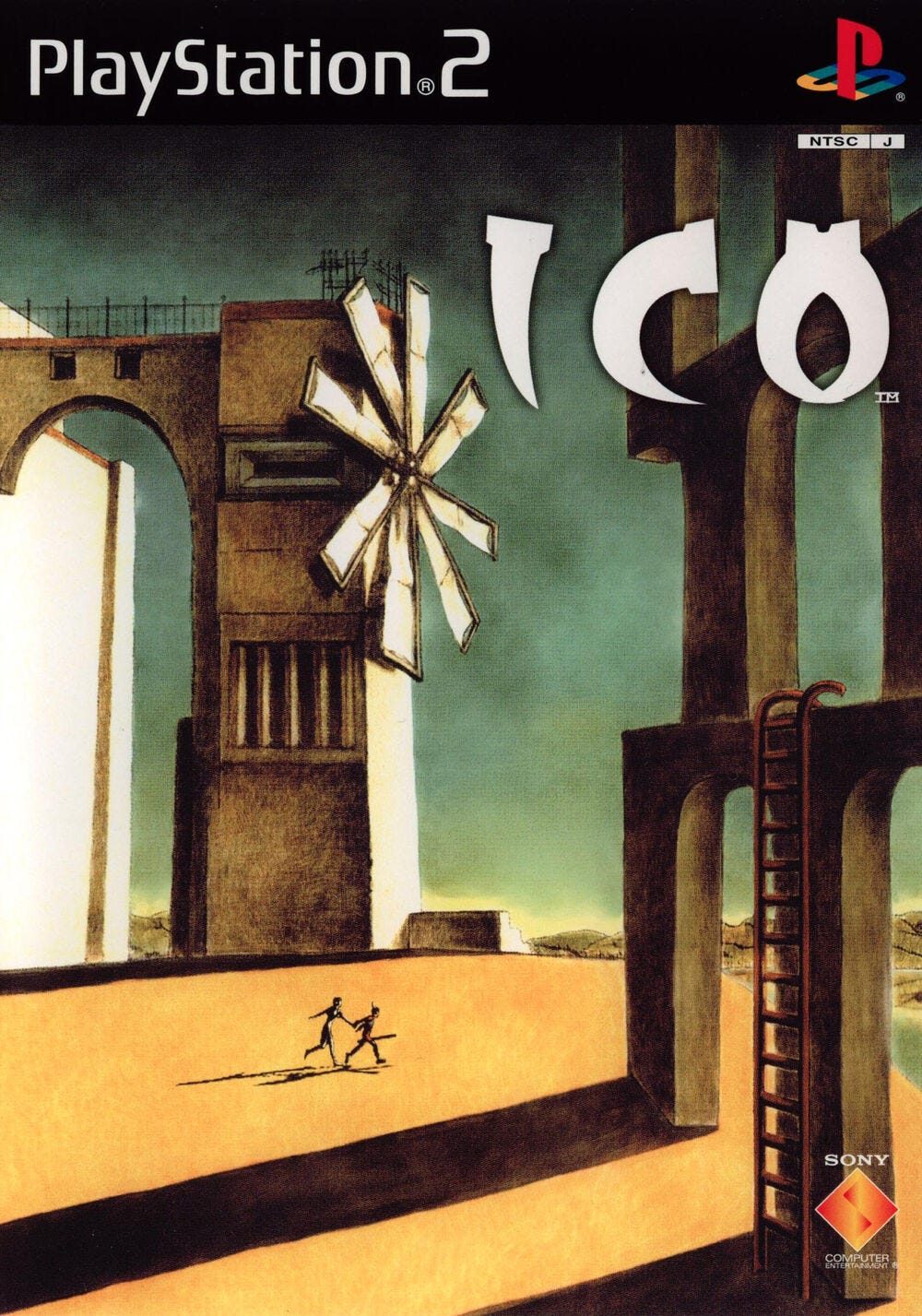

My big feeling reading Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow was that this is obviously a great story and Zevin is obviously a great writer, but she should have spent another year editing and tightening it. The bones of what make it popular are in here: interesting characters, big emotional payoffs (the death of one character was heart breaking!), a big topic that is underexplored in literary fiction which is video games, and interesting examples of those game cribbed from real games (e.g., Doom, Ico, Maple Story). But the story implied by the book feels better than the book itself. I wonder if a note I would give to this as a manuscript would be to write deeper, fewer scenes, to not skip over as much long time and to show us the problems faced in one creative project instead of jumping so much between them.

A few others I read this year that are worth jotting down smaller notes on:

The Guest by Emma Cline: I loved this second novel by Emma Cline, which bucked the trend I mentioned earlier of highly celebrated debuts having regression-to-the-mean sophomore productions. Her aimless cool girl narrator, who seems perfect in a post-My Year of Rest and Relaxation world to be popular with readers, is compelling with her compulsive behavior. The setting of The Hamptons with its money and perfect lawns is great, and the way the story feels clockwork small, with characters reappearing in convenient ways, feels appropriate to the small insulated community you'd expect to find there. This was a "hang out" novel, I could open it and re-read any chapter and enjoy our breezy poor narrator. I loved the tense pickles she kept finding herself in. I liked it more than The Girls, which I also read this year.

Farewell to Fifth Avenue by Cornelius Vanderbilt, IV: This is a memoir by the fourth generation of the Vanderbilt family, a fascinating man who lived in the most lavish privileged possible life in America in the first half of the 20th century. "Neil" Vanderbilt is writing his own mythology, so it's hard not to wonder the spin he's putting on things, but when the facts of the story are as interesting as they are, it's nice to have a narrator who is such a good writer. Read Neil as he, as a young child, tries to run away from home to the White House and gets a personal response back from Roosevelt. Read him sunning on a yacht with the Kaiser of Germany before WWI. Read him hanging out with Al Capone, the Pope, Hitler!

How to Love Your Daughter by Hila Blum: The saddest book I read this year, deep and gutting story about a woman trying to find love and connection with her daughter and the struggles she faces. The story is interesting in its careful, emotional writing, but also its structure: it feels like Blum is laying everything out on the table. There are no manipulative jumps, rhetoric, no distance between what we read and what it feels like Blum is trying to communicate. Irony is great, distance is fun, but when you have an intelligent, thoughtful, well spoken narrator and she sits besides you and shares, that is a specific pleasure (the other book I think of as typical of this way is the great The Friend by Sigrid Nunez). Also noteworthy for its total disinterest in a classic three act structure, love it. Resolution is nowhere in this story. I like it 100 times more than Crying in H Mart.

Bear by Marian Engel: Someone on an internet forum called this the Great Canadian Novel, probably when I was in high school, and I'm glad I finally read it. Way more complex than the premise suggests, which is simply easily stated as "woman has sex with a bear." I always assumed that the bear would be a symbol for the beauty of nature, or the way that one should better convene with nature rather than unnatural bad relationships. Or that the bear would be a metaphor for men and their animal-ness, or a foil for men in a caring giant bear versus mean uncaring men. But it's not any of those things. This is not a story in which is is unequivocally good to have sex with a bear (good!). It's much more about colonization, the bad behavior that comes with loneliness, beautifully amazingly written.

The Disappointment Artist by Jonathan Lethem: Great essays, but the standout chronicles his relationship to the film The Searchers. I love his deeply honest sharing about how he pretentiously sought to make this film part of his identity, and how its messy themes have made it a lifelong thinking stone. A great, honest account of how great pieces of art stay with us and are useful.

Penance by Eliza Clark: I mentioned this already, but another great sophomore novel. Eliza Clark does something I praised Makkai for not doing in I Have Some Questions for You. I liked Makkai's willingness to confront her murder head on, to tell the details of the case as we know them, to put our POV right next to Bodie Kane and know what she knows. But I also like, maybe even more, Clark's willingness to not look straight on at the murder at all. Her story only slowly gives us the facts of the case, and never in center focus. Instead, we get fractured psychological snippets of the lives of the girls who killed their friend, shown through biased clips from podcasts, interviews with known people, and the highly subjective narrator who is (like Bodie Kane) inserting himself into a crime story he has no connection to (at least, it seems that way. Clark makes great, straightforward, sincere work of connecting our narrator's dead daughter to the case in a beautiful way). The stories of the girls are so richly drawn, she keeps adding new elements that are fun. It's nice to see things like Tumblr, Slender Man, Fandom, Pokemon show up in a literary novel with as much skill as this one. Very very good!

The Expendable Man by Dorothy B. Hughes: This crime novel from 1963 does something I haven't seen many books do: introduce a large twist a quarter of the way through. My thoughts reading the story until the twist felt like exactly what the author would have outline a reader to believe, I felt perfectly amazingly duped (it's worth reading this book: skip the rest of the paragraph if you don't want to know). The story opens with a UCLA doctor, Hugh, driving out east towards Phoenix to see his family. He stops and picks up a hitchhiking girl who is clearly younger than she claims to be. That there is tension between Hugh and the girl makes sense, maybe he is ashamed to be attracted to her, maybe he is nervous she will rob him. But the story pays close weird attention to Hugh looking around to see who is seeing them. I chalked it off to melodrama or bad writing. By the time she shows up at his hotel room in Phoenix, we get a mini-twist: she asks him to perform an abortion (illegal in their world). It feels like it retroactively explains some of why the story has Hugh so jittery. The next day, her body is found by the police. At this point in the story, Hugh gets hyper paranoid. As a reader, it's distancing: why is this guy so worried? Why does he ruin all his time with his family worrying about the fact that this random girl has been killed and what role he'll play in the future? When cops come to question him, the author drops the twist: we have never had a single detail about Hugh's race. It's the cops dropping a slur that gives us the answer. It completely inverts how you've been reading the story so far, it flips everything inside out. And it lets the rest of the story explore entirely new themes that were hidden so far. Loved it. There's a great romance here too.

This is the penultimate post of this series; I’ll wrap things up for 2023 in the next post. In writing these, I enjoyed getting the chance to expound on what I enjoyed and thought about what I read in 2023. There are five other books I loved but did not find something huge to say about (either before or in final post): Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan, Bluebeard's Castle by Anna Biller, Y/N by Esther Yi, Tom Lake by Ann Patchett, and Deliver Me by Elle Nash.

Click here for the eighth and final post of 2023 Reading in Review when it’s posted and subscribe below to get email alerts for new posts. Full list of works discussed here.