This is the first section of Chase’s 2023 Reading in Review, a series of posts where Chase reflects on books read in 2023. The reviews don’t assume you have read the works, and don’t spoil their experiences. This section primarily discusses:

Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

Michael Christie’s Greenwood

Jane Alison’s Meander, Spiral, Explode

Full list of works discussed here.

The best thing I read this year was Annie Dillard's nonfiction Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. Dillard, in her late 20s, writes and reflects on the natural world as observed and considered from her remote home in Virginia in the early 1970s.

Because Dillard is a Thoreau scholar intentionally writing in his genre, I first read Henry David Thoreau's Walden, for the first time. My pre-association with that story was the hypocrisy people point out on Twitter and Tumblr about it: that Thoreau's supposed self-reliance and loneliness in the woods was supplemented by the access to society that he still maintained, someone doing his laundry etc, privilege masquerading as rugged individualism. Walden ends up not being that challenge. It is not a YouTube video titled, "I Actually Lived in The Woods With No Help," so all that ends up mattering less than expected. What I found and liked in Walden was his interest in authenticity, not as a style ("I am being authentic in how I dress, speak, present," which is how I encounter authenticity most day-to-day in my own life), but as a way to experience things. Thoreau takes seriously the matters that make up his life: authenticity as about attention.

I was still more excited by Dillard, whose meditations on what she observes in nature feels pro-social, even as it raises challenges about how we might live. Take this scene early in her book where she describes seeing a frog in the water:

He didn’t jump; I crept closer. At last I knelt on the island’s winter killed grass, lost, dumbstruck, staring at the frog in the creek just four feet away. He was a very small frog with wide, dull eyes. And just as I looked at him, he slowly crumpled and began to sag. The spirit vanished from his eyes as if snuffed. His skin emptied and drooped; his very skull seemed to collapse and settle like a kicked tent. He was shrinking before my eyes like a deflating football. I watched the taut, glistening skin on his shoulders ruck, and rumple, and fall. Soon, part of his skin, formless as a pricked balloon, lay in floating folds like bright scum on top of the water: it was a monstrous and terrifying thing. I gaped bewildered, appalled. An oval shadow hung in the water behind the drained frog; then the shadow glided away. The frog skin bag started to sink.

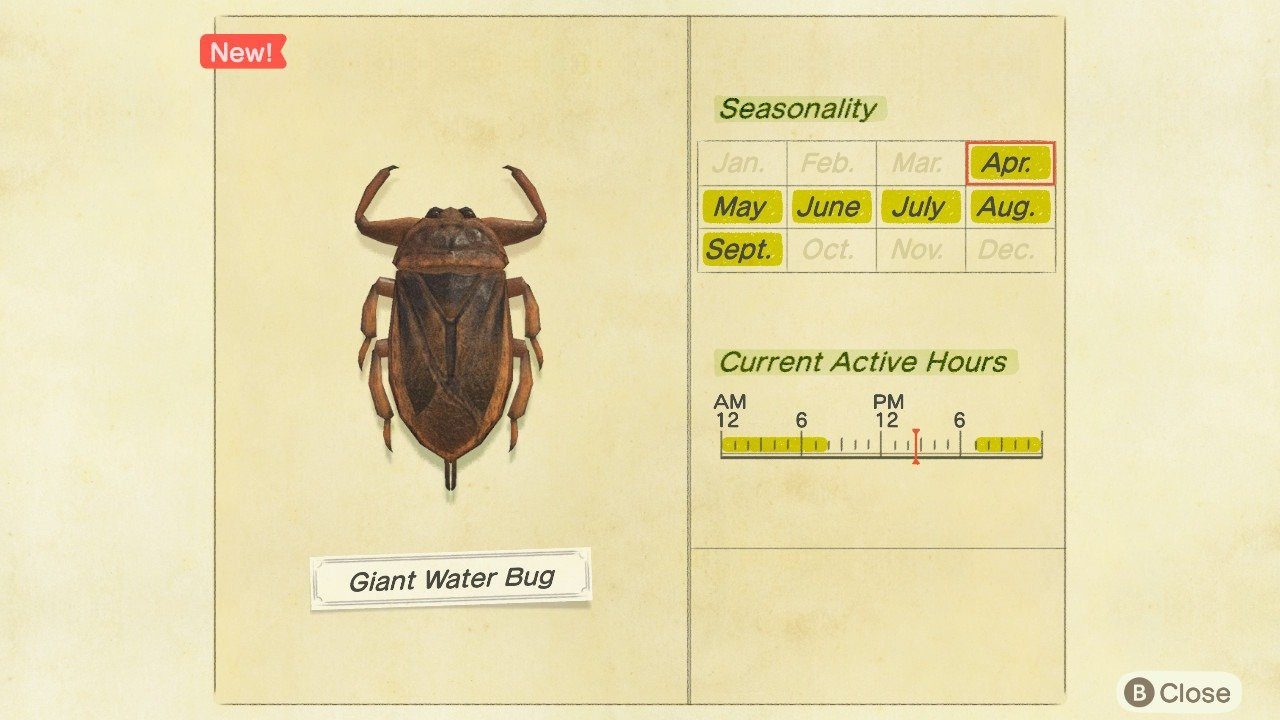

I had read about the giant water bug, but never seen one. “Giant water bug” is really the name of the creature, which is an enormous, heavy-bodied brown bug. It eats insects, tadpoles, fish, and frogs. Its grasping forelegs are mighty and hooked inward. It seizes a victim with these legs, hugs it tight, and paralyzes it with enzymes injected during a vicious bite. That one bite is the only bite it ever takes. Through the puncture shoot the poisons that dissolve the victim’s muscles and bones and organs—all but the skin—and through it the giant water bug sucks out the victim’s body, reduced to a juice. This event is quite common in warm fresh water. The frog I saw was being sucked by a giant water bug. I had been kneeling on the island grass; when the unrecognizable flap of frog skin settled on the creek bottom, swaying, I stood up and brushed the knees of my pants. I couldn’t catch my breath.

Dillard has retreated into nature (quiet, lonely, natural, safe, where we came from) and found violence there. 100 years after Thoreau, during a century in which we saw the atom bomb and the Holocaust, horrible manmade terrors, Dillard looks at nature and sees more terror. She starts her book out revoking a common (if unfair) interpretation of Thoreau: if only we could go away from society and into nature, all would be well. Not so!

Dillard keeps exploring this idea on her chapter on fecundity, which begins with her pointing out that an enormous field of flowers does not disgust us, but it is unnerving to imagine a field the same size with the same density of any animal organisms (bugs, wriggling chipmunks). Dillard zeroes in on the terror of it:

I don’t know what it is about fecundity that so appalls. I suppose it is the teeming evidence that birth and growth, which we value, are ubiquitous and blind, that life itself is so astonishingly cheap, that nature is as careless as it is bountiful, and that with extravagance goes a crushing waste that will one day include our own cheap lives, Henle’s loops and all. Every glistening egg is a memento mori.

This is fecundity, nature's goal for endless growth. Not only is this again something natural made terrifying, not only is this natural world completely untouched by humans, but it suggests that in attempting to solve a problem of scarcity, in growing, here come new problems. It seems like work can never be complete. Success as a kind of failure.

This feels a big theme of the 20th century found as a phenomenon that existed millennia before industrial society and that will exist millennia after it. The 20th century I refer to here is the one that seemed to see so much "progress" (e.g., seemingly equitable new social structures in Russia or China, technological progress, civilization) that turned out to beget new/old problems (e.g., mechanized death, corruption, alienation, ecological jeopardy). In Dillard's account, the problems of modernity begin not to feel like specifically modern problems at all.

I had Pilgrim on my "to read" list for most of 2022. I found it when I was looking up the SAT, trying to see if being a decade out of high school would make me better or worse at answering its questions. A reading section used the opening page from Dillard's book:

I used to have a cat, an old fighting tom, who would jump through the open window by my bed in the middle of the night and land on my chest. I’d half-awaken. He’d stick his skull under my nose and purr, stinking of urine and blood. Some nights he kneaded my bare chest with his front paws, powerfully, arching his back, as if sharpening his claws, or pummeling a mother for milk. And some mornings I’d wake in daylight to find my body covered with paw prints in blood; I looked as though I’d been painted with roses.

It was hot, so hot the mirror felt warm. I washed before the mirror in a daze, my twisted summer sleep still hung about me like sea kelp. What blood was this, and what roses? It could have been the rose of union, the blood of murder, or the rose of beauty bare and the blood of some unspeakable sacrifice or birth. The sign on my body could have been an emblem or a stain, the keys to the kingdom or the mark of Cain. I never knew. I never knew as I washed, and the blood streaked, faded, and finally disappeared, whether I’d purified myself or ruined the blood sign of the passover. We wake, if we ever wake at all, to mystery, rumors of death, beauty, violence…. “Seem like we’re just set down here,” a woman said to me recently, “and don’t nobody know why.”

These are morning matters, pictures you dream as the final wave heaves you up on the sand to the bright light and drying air. You remember pressure, and a curved sleep you rested against, soft, like a scallop in its shell. But the air hardens your skin; you stand; you leave the lighted shore to explore some dim headland, and soon you’re lost in the leafy interior, intent, remembering nothing.

It's great writing, plump with Dillard's sense of nature as dangerous and yet also nurturing. The cat feels like a friend, a creature of mystery, a menstrual metaphor, and her response, her surrender to nature as something powerful, larger than herself, often terrible, comes across as neither quite romantic nor nihilistic.

And the prose is impressive: how she moves between 1st and 2nd person over the paragraph, the way she introduces a contextless woman with a contextless quote that does not feel non sequitur. I don't think I would have written the word "mirror" twice so close to each other in the second paragraph-- but the second time, she's used it to explain why we met a mirror in the first sentence. It's very good! And she was 27 when this book came out.

Another of the books I most enjoyed reading this year had a similarly subversive take on nature. Greenwood by Michael Christie seems unfortunate in that it shares a similar pitch to The Overstory by Richard Powers, which was very celebrated a few years ago when it came out. But beyond the appreciation for trees and a non-linear multi-character structure, the books don't feel similar in their prose at all (Powers is so scientific, Christie comes off warmer), or in their themes.

Greenwood (like The Overstory) ends up being a short story collection and a novel together. There are plenty of books like this where the stories intersect (I read many just this year: Lore Segal's Shakespeare's Kitchen, Grace Paley's Enormous Changes at the Last Minute, Brandon Taylor's The Late Americans, Ann Patchett's Commonwealth-- of all I read this year, Commonwealth was a favorite read). Greenwood is different than just a novel with many characters because it tells its story in discrete blocks of time epochs.

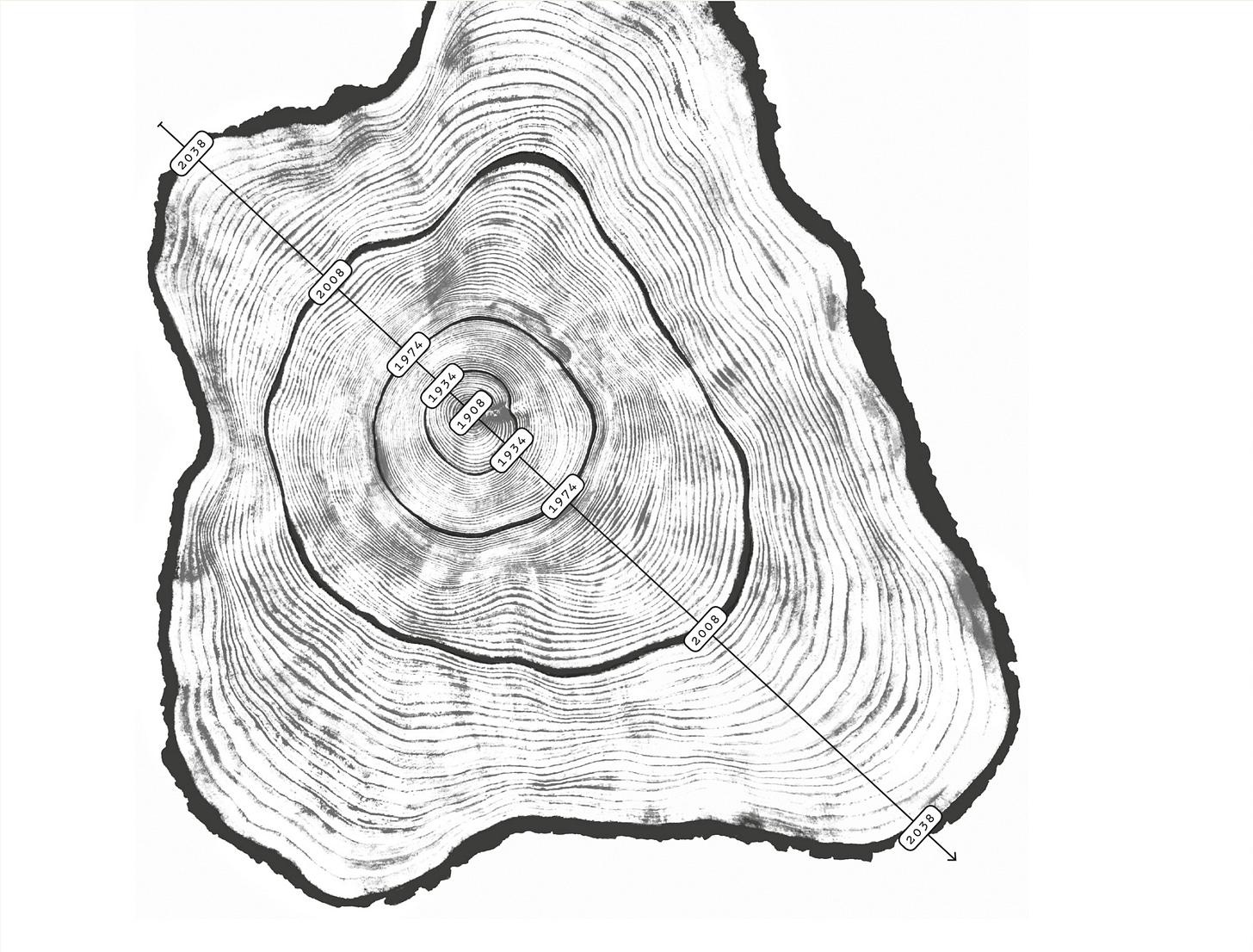

This is the same structure as David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas: it has a few chronologically separated episodes for the first half of the book and then retreats backwards, so that the characters you meet at the beginning do not return again until the final chapter. Christie shows you at the beginning that this is meant to mirror the rings of a tree moved through: outer ring, then a ring deeper, until the center, then all the rings again in reverse order until you end back at the outmost. The key of movement is time: as you progress in, you go back in time, and then out brings you back forward.

I think it's interesting how influential the Cloud Atlas structure has been. I read a lot of these novels, good celebrated novels, that seem to have taken from it (e.g., the both excellent Yaa Gyasi's Homegoing and Susan Barker's The Incarnations, and just this year I also read Geraldine Brooks' Horse and Daniel Mason's very very good North Woods). I don't know if it's ahistorical to name the category after Cloud Atlas, but books like Greenwood make me wonder if we will look back at the first few decades of the 21st century and see this as a proper genre of the time.

As for Greenwood, it takes its plot seriously in a Dickensian, clockwork way (and its focus on revealing a character’s inheritance feels 19th century novel). I enjoyed its big emotional moments, even if its insistence on tying tight every string could come across artificial (I enjoyed this Andrew Martin review of Nathan Hill's Wellness, in which he lobbies the same claim against Hill).

Here are two things that make Greenwood excellent. The first is its more nuanced understanding of nature. Like Dillard, Greenwood's natural world is both wonderous and dangerous. For a story with a big chunk in a post-climate-change world, Greenwood sure does take seriously the idea that sometimes we should cut trees down. This is a complex note in an era where climate change literature has political urgency. The loggermen characters might be in another story easy villains. Instead, here they more complex. Brothers Harris and Everett Greenwood compose such a core of the novel that sometimes the other sections feel only supportive. I wonder if there's an earlier draft of this book that does not have the Cloud Atlas structure and which just follows Harris and Everett.

The other feat Christie accomplishes is in his storytelling. Midway through, he sets a scene in which one character must convince another to sign away something valuable. This character proposes he win this in arm wrestling. In outline, in summary, this feels so ridiculous and inappropriate at the narrative level. You can't build a plot point around something so fickle! And yet, in that scene, Christie makes it feel so real! So earned! So dramatic! I can't explain how he got away with it (David Lynch does this in The Return as well).

Greenwood's non-linear Cloud Atlas structure plays with what is otherwise a traditional story, fit for Dickens. The structure is interesting but it doesn’t radicalize the story or its telling, just like Wellness. Another favorite book I read this year investigated what it would mean to commit more seriously to other modes of storytelling, where you might not need to tie every string as tightly as Christie does.

Jane Alison's Meander, Spiral, Explode is a nonfiction craft book about creative writing that explores the traditional three-act structure as only one option amongst a menu. It's a better book than one which simply points out criticisms of the traditional template for storytelling because it does the work of building out alternatives in beautiful detail.

Alison looks for inspiration in nature (like Dillard) and finds (as many before her have) that there are tense, interesting shapes for crafting a story. The wave (her name for the three-act) fits in its place besides other options: the spiral, the radial, the network.

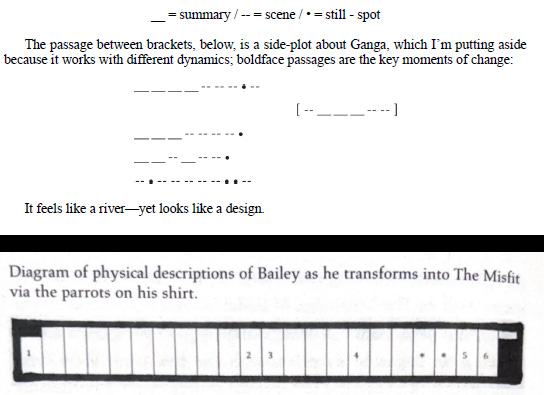

See how Alison reads Vikram Chandra's “Shakti” for moments of summary, scene, and stillness. She diagrams using dashes and dots (much like Lucy Corin did in her excellent essay “Material” about "A Good Man is Hard to Find" in one of the two Tin House Writers Notebook craft books I read this year), showing how the pacing of what happens in the story comes off as structurally necessary to delivering the effect. Is Alison painting an accurate picture of the story with every symbol in her diagram? Even if you disagree with how she characterizes a moment, thinking this deeply about what is happening in the rhythm of a story is good sophisticated work. Is she right about Chandra's intent and writing process for the piece? Again, who cares. Alison correctly points out that the structures in nature may or may not be intentional. We can intuit how a wave works, a network, an explosion.

These are not dictums about how writing must be. They're prompts towards a right direction. Other good prompts I enjoyed in readings this year: Charles Baxter in The Art of Subtext notes to give a character something incredible and desirable that they don't want (e.g., a robust love life is a good example, I'm thinking of the lonely yet romantically successful characters in Lorrie Moore's protagonist of "Two Boys" and Toby in Fleishman is in Trouble). This could be Dillard and fecundity again: “the troubles with success.” Joan Silber in The Art of Time in Fiction suggests starting a clock, any clock whatsoever, even if there is no pressure in its deadline (e.g., two films I watched this month have clear school-related clocks: The Holdovers which is set in the limited time of winter break, and May December which promises a high school graduation). A clock structures time, even if there are no consequences to the clock running out.

These prompts (pointing towards a right direction) are more interesting than rules. Lee Seong-bok puts it well in Indeterminate Inflorescence when he notes that when stalks of flowers bloom in order "top to bottom," they have limited growth, but when they bloom "bottom to top" it's unrestricted (Dillard might warn against such fecundity). There's a good section in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (more on it in a later section) which shares a teacher's personal doubt after a student questions prescriptive writing rules:

The rule was pasted on to the writing after the writing was all done. It was post hoc, after the fact, instead of prior to the fact. And he became convinced that all the writers the students were supposed to mimic wrote without rules, putting down whatever sounded right, then going back to see if it still sounded right and changing it if it didn’t. There were some who apparently wrote with calculating premeditation because that’s the way their product looked. But that seemed to him to be a very poor way to look. It had a certain syrup, as Gertrude Stein once said, but it didn’t pour.

That's a funny subversion of the image E.M. Forster puts out in Aspects of the Novel, in which he asks that you imagine all the writers of all of history sitting together in one room, writing together, in conversation. Maybe they wouldn't have much, if anything, to say to one another! Maybe it's all instinct!

A theme for me this year is precisely this. Cormac McCarthy notes in The Passenger (read last year) that mathematics is performed by instinct, that the thing that clicks when one finally discovers the answer to a challenge is clearly irrational (Gertrude Stein: "What is the current that makes machinery?"). There is something (maybe a "passenger," per McCarthy's title, though it's funny that this is also the main metaphor used in the TV show Dexter) that the writer/thinker is nurturing, which is not the conscious mind, which is responsible for a huge amount (if not all) of the creation.

The work is to keep this other you, this nonconscious you, alive and thriving. Perhaps that's why Charles R. Johnson in The Way of the Writer suggests that all writers read the dictionary cover to cover. "Where else are you going to get your words?" he asks, cheekily (I’m paraphrasing), but maybe you do just have to swallow things inside you so that this other "passenger" can digest and use it.

Rick Rubin's The Creative Act knows this well. His anecdotes and suggestions are all focused on how you as a conscious mind can set up the internal creating party to do that work effectively. I particularly like the anecdote he tells of the college basketball coach who taught his players how to properly tie their shoes. When you're not in the middle of creating, it becomes important to prepare so that when you are, you can act on instinct and not get tripped up.

Beyond her work documenting these useful creative structures for storytelling, Jane Alison provides a great syllabus of different, imaginative works. I read and loved Nicholson Baker's The Mezzanine, which has a Curb Your Enthusiasm interest in detailing internal chatter and expressing how one thinks in day-to-day (our character, rising up an escalator to his office on the mezzanine, thinks about the relative rates of his shoe laces, why one shoe lace might break before the other, if there are things one does which puts more stress on one shoe lace or not). This is the detailed minute plasma that connects the creative passenger and the steward, the one that has to walk, and buy shoelaces, and go to work. Kelly Reichardt’s Showing Up documents this same stuff beautifully as well.

Click here for the second post of 2023 Reading in Review when it’s posted and subscribe below to get email alerts for new posts. Full list of works discussed here.