This is the third section of Chase’s 2023 Reading in Review, a series of posts where Chase reflects on books read in 2023. The first is here. The reviews don’t assume you have read the works, and don’t spoil their experiences. This section primarily discusses:

Benjamin Labatut’s When We Cease to Understand the World

Tom Wolfe’s Bonfire of the Vanities

Naomi Klein’s No Logo

Full list of works discussed here.

The “modern” I want to talk about is a hypothesis. It’s the idea (a proposed hypothetical idea) that something "special" about the 20th century (vs any time before it) is that industrialization begot technology and urbanization which changed relationships to community and the natural world. We could dream of building skyscrapers now, and actually do it. Medicine began changing lifespans and quality of life. In intellectual matters, the art community broadened how and what kind of art could be created, psychology began to map out how we think and behave, and mathematics standardized. At the same time, we found limits: the technological progress of Nazi Germany didn't prevent (and actually enhanced) the genocide committed, America used its technology to create the world-ending atom bomb. Less grandly, we have things like mathematical incompleteness, which proved math axioms would never be exhaustive, and the unconscious of human behavior proved to be tricky to navigate.

Much of the intellectual journey of that story takes place in the quantum world. One of the best books I read in college was The Making of the Atom Bomb by Richard Rhodes, which documents how a niche and jovial community of scientists slowly progressed their field until it was clear to the mere hundreds of them that they had stumbled onto one of the most significant developments in all of history.

A great book I read this year which tackles this is Benjamin Labatut's When We Cease to Understand the World. Somewhere between fiction and essay, the book looks at the thought processes and historical moments of early 20th century scientific developments. He tells the crude story I told a paragraph ago beautifully in the opening chapter, “Prussian Blue”, in which he juxtaposes facts about paint color sourcing (which is only possible in a modern, connected, technologically enabled world), the art implications of new paints (which points to what was expanding in taste and understanding), and ultimately, the way the same technologies enabled the violence of modern warfare and genocide. This is a great encapsulation of that tale done in a genre of essay that I find is elsewhere more poorly done than well done. There are a lot of bad essays that attempt to be restrained in simply putting facts next to one another, failing to assert a point of view (Labatut is not guilty of this).

His later chapters get inside the heads of major scientists of the first half of the 20th century, and again, his writing succeeds at a challenge most would fail at: communicating inside the minds of specified, technical folks without getting bogged down or staying too surface.

His theme is in the title: what happens when we extend our knowledge into forms that stop making intuitive sense? Particles in multiple places, space curved and time relative, mathematics stretching across diverse new types of numbers.

My quibble isn't with Labtut or his book, which is great, but with the hypothesis itself. It's only shocking that modernity has produced "incomprehensible" theories if you take the position that it should have produced comprehensible ones. Is it novel that we discovered that things may be more mysterious than we thought? (Dillard pokes a head out). Should we conclude that we are in a new phase of intellectual history where we are seeing limitations "for the first time?" It's not the first time. Not being able to perfectly comprehend how everything works is not a new phenomenon, it's maybe the oldest one! Annie Dillard in Pilgrim at Tinker Creek looks at the wriggling field of bugs and says: others and other species have been dealing with this for far longer than a few decades.

That modernism happened (whether it was new or not) is undeniable. In books, clearly, there is something different about the prose of Henry James and later otherwise similar writers. Time is funny. There is far less time between James's Turn of the Screw and a novel like John Dos Passos's Manhattan Transfer (a favorite of mine this year), and yet James feels old and Dos Passos's novel feels like it could have been written yesterday.

I don’t know if I’m the one to intellectualize “why do some styles feel contemporary and others old-fashioned,” but there is something there. Everyone loves Zinaida Serebriakova's "Self-portrait at the Dressing Table" because it looks like a selfie, even though it was painted in 1909.

What makes this effect so strong in Manhattan Transfer is not just the prose, which is stream-of-conscious and unaffected, but the lifestyle of the characters. They have complex dating and sexual histories which are casual and informally defined, like many of ours, and they go to work, climb stairs to their apartments, quibble about money, take the subway. It feels remarkable that this was written in 1925, nearly 100 years ago, but that's what I'm trying to get at: why should life in 1925 necessarily feel all that different?

There's traces of the "way of life"-ness of Manhattan Transfer in multiple other works I read and enjoyed this year. Grace Paley's 1974 Enormous Changes at the Last Minute follows city-bound neighbors who feel like your neighbors. And the biggest book I read this year, William Gaddis's excellent 1955 The Recognitions, feels like it inherited the mission of telling a story about New York life from Dos Passos. Gaddis's ability to write realistic, sonic, amazing dialogue is correctly celebrated (I loved JR when I read it in 2015). It is worth carefully studying how he composes these massive party scenes, where characters are drunk and incoherent, babbling sometimes to each other and to themselves, where they speak with base intents and still reveal true things they don't want to reveal.

The comedy of The Recognitions is incredible. I love the little details like the Mickey Mouse watch, and the book has the funniest scene in anything I read this year (when a character shows up expecting to meet his estranged father, but actually meets someone attempting to launder counterfeit bills, and he interprets the bills as a gift of resources from his father. Other contenders for funniest moment in a book I read this year: Nathan Hill's Wellness's Jack attempting to get pornography off a computer by photographing it, and then when the prints are discovered, exhibiting it as a work that comments on the commodification of women's bodies. Greenwood's aforementioned arm wrestling. A pre-teen boy who thinks he has to pick what he wants to be when he grows up and gets into a tizzy with the weight of the choice in Camille Bordas How to Behave in a Crowd. The way General Sash talks about the parade in Flannery O'Connor's "A Late Encounter with the Enemy"). It's clear that what Gaddis did was take much of Dos Passos did and find a way for it to be an entire genre. I can't imagine Pynchon without this, for example.

Much of the story of modernization, what has happened between Thoreau and Dillard, has to do with money and finances. The world has become a financial world, where we can account for people and resources moving in complex global systems. The pair of books I read that best told this story were a novel and a nonfiction book, both classics written at the very end of the 20th century.

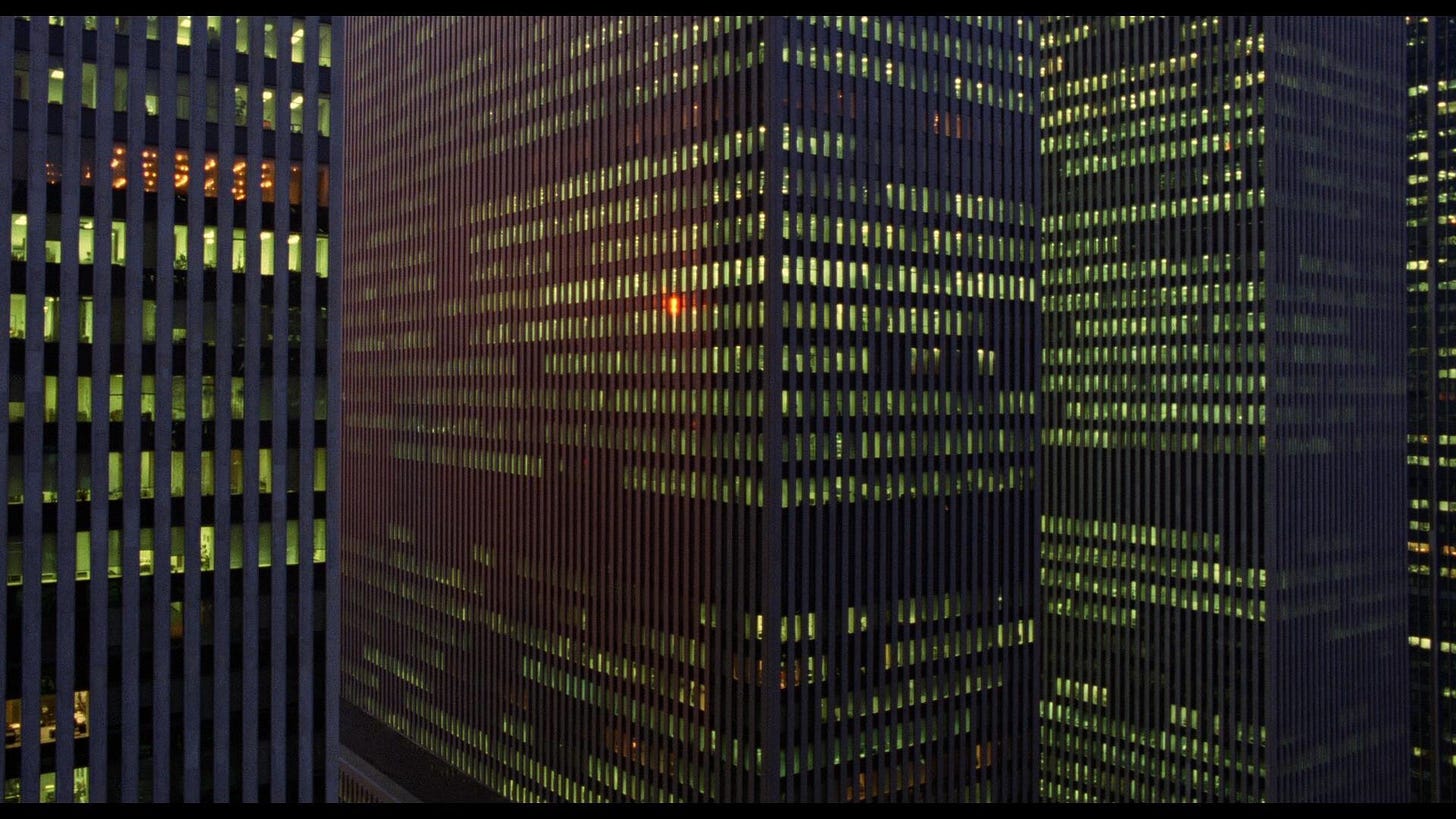

Tom Wolfe's Bonfire of the Vanities is the novel. After a great prologue which sets the thematic stakes, the first chapter is so immediately stuffed with great storytelling.

At that very moment, in the very sort of Park Avenue co-op apartment that so obsessed the Mayor . . . twelve-foot ceilings . . . two wings, one for the white Anglo-Saxon Protestants who own the place and one for the help . . . Sherman McCoy was kneeling in his front hall trying to put a leash on a dachshund. The floor was a deep green marble, and it went on and on. It led to a five-foot-wide walnut staircase that swept up in a sumptuous curve to the floor above. It was the sort of apartment the mere thought of which ignites flames of greed and covetousness under people all over New York and, for that matter, all over the world. But Sherman burned only with the urge to get out of this fabulous spread of his for thirty minutes.

So here he was, down on both knees, struggling with a dog. The dachshund, he figured, was his exit visa.

Looking at Sherman McCoy, hunched over like that and dressed the way he was, in his checked shirt, khaki pants, and leather boating moccasins, you would have never guessed what an imposing figure he usually cut. Still young . . . thirty-eight years old ... tall . . . almost six-one . . . terrific posture . . . terrific to the point of imperious ... as imperious as his daddy, the Lion of Dunning Sponget ... a full head of sandy-brown hair ... a long nose ... a prominent chin ... He was proud of his chin. The McCoy chin; the Lion had it, too. It was a manly chin, a big round chin such as Yale men used to have in those drawings by Gibson and Leyendecker, an aristocratic chin, if you want to know what Sherman thought. He was a Yale man himself.

Here we get the setting of Sherman McCoy's lavish Park Avenue apartment, explaining the kind of life he leads and the stakes of that life, we get the physical details of his large and statuesque body, we get the comedy of the cubist contortions he's doing to get his dog on a leash to go outside, and we get the nagging urgent something that's in his chest: why does he want to go outside so badly? That urge (it's to visit a mistress) pushes us to the inciting incident a few chapters away. It does everything you're supposed to do when opening a novel, and it is a pleasure to read.

Sherman McCoy's world is rooted in his point of view. Wolfe's style is very readable and energetic: close limited third person, with the kind of narratorly story-flourishes that push the story along (e.g., "so here he was."). I love the way he crystalizes aspects of McCoy's world view. McCoy is a bond trader, a well paid, elite-thinking power man, and Wolfe takes this self-belief and he bottles it up in a phrase that McCoy repeats to himself over and over: he is a Master of the Universe. This is a great narrative trick, because it is a powerful phrase in-and-of-itself, and it lets Wolfe repeat that as shorthand, much like the epithets that J.K. Rowling is good at doing in Harry Potter (e.g., she can state simply: red haired child, child with buck teeth, adult with greasy hair-- she's good at the shorthand). Wolfe does this again with a great detail, like calling one character “the girl with brown lipstick” (it shows she is an avant garde, a subeversive, an artist, exotic).

What makes Sherman McCoy a self-claimed "Master of the Universe" is his ability to handle large amounts of money at his finance job. This financial power man is highly modern, it's the financial stuff that defines why we can have technology and global trade and imported bananas et cetera. But McCoy's styling are also pre-modern: there were men like him in Rome, there were men like him in the medieval Vatican.

The reckoning McCoy faces, which is both timelessly political and topically related to the justice goals of today's world, is what's different, not his commanding of power.

The nonfiction book I enjoyed with Wolfe's was Naomi Klein's No Logo. Klein is studying the marketing and branding of the 1980s and 90s, the end of the century, when we've had 90 years of 20th century thinking behind us. What she finds feels different in quality than what was happening with the industrial times of factories and building skyscrapers and inventing the death-tech of WWII.

Her observations about Nike are maybe the best encapsulation. A classical shoe company would make and sell shoes. They would come up with ideas for shoes, find the supplies for them, scale up production, market and then sell those shoes to people. They would employ the kinds of people necessary to ensure that happens: legal, IT, HR, finance, procurement, creative, quality assurance, real estate.

Instead, Klein documents how Nike has stopped doing as much as they can possibly stop doing: manufacturing happens with contractors, agencies handle marketing, etc. At every step, Nike looks to reduce overhead and cost on its balance sheet by simplifying away from physical processes. They become somewhere between an idea and an emotion. In a brand-forward world, the best companies won't manufacture or handle anything at all.

Underneath these are the stuff-of-the-world: sweat shops which need not appear ethical because they have no brand. They become precarious contractors who are dependent on the parent brand for their business.

With the rise of brands, you get another entity rising with it: big box wholesale retailers who focus on pricing and promotion where the brands do not. Shopping districts re-organize into places where the brands are sold (flashy, central areas) and wholesale retailers take space on the margins of town.

The theory of this is simple and well articulated. She then goes forward and watches each of the crawling consequences of organizing the world this way, from the way brands accelerate their redefinition given their lack of ties to anything physical (i.e., you can't be boring if you no longer own anything but your name, what else are you to do with your time but constantly churn out new creative?), spend lots of money to show up places like schools, fight to win the future minds because that's all you are. She does a great job documenting the ways this approach makes you vulnerable as well. Scandal matter more when all you are is reputation.

I love her anthropology of our world, her ruthless and strong political lens. Organizing under brands is not dissimilar from the differently-originating keiretsu system in Japan (I read the book Keiretsu by Kenichi Miyashita and David Russell about them this year), where giant conglomerates exert pressure onto networks of thousands of struggling subcontractors. Another great and similar read was Carl Vigeland's Great Good Fortune, which documents the over-financialization of Harvard University in the late 20th century.

Shortly after No Logo, I read Maggie Bullock's history of J. Crew: The Kingdom of Prep. Bullock is a great storyteller and writer and I am excited to read anything she chooses to write next. Most of all, I enjoyed watching in case study many of the dynamics that Klein laid out in No Logo. The story of founding J. Crew is exciting: her account of the father and daughter duo of Arthur and Emily Cinader showcases the father's highly-tactical catalog marketing tactics with the daughter's personal style and taste (and sense of brand). I like the anecdote that Arthur was so maniacal about the company's presentation and success that he proofread every single issue of their catalog himself (the idea of a catalog as a company's core selling capability, as a viable growth sales channel, is also funny in comparing it to today). I also like the anecdote that Emily's life stories seemed fake and copywritten until there were photos produced which showed Emily did have an actually kind of preppy ideal childhood. Their sense of class is so interesting contrasted when private equity puts in Mickey Drexler, whose ambition and excitement about business feels of a different order, more contemporary, more financialized. I like his quirks and affections, his excitement about retail vs catalog, so different than the Cinaders. He’s well drawn, such as the way Bullock accounts him holding himself in meetings, the loudspeaker he put outside his office so he could speak to the company at once. The last era, where Bullock puts Jenna Lyons in the center stage, feels like an important historical moment: the clothes J. Crew was making under Lyons in the late aughts and early 2010s feel like the kind of clothes we will think of as typical of that era. Lyons showed up on HBO's Girls! All in all, I found it funny how much activity happened at J. Crew and yet how little financial success they ever enjoyed. They went bankrupted so many times, it seems like no one has ever turned all this hubabaloo into an actually successful business.

What's documented by Klein and in Bullock's story of J. Crew feels more than modern: that this is how our current world is composed and may point towards what's about to happen.

I also watched Adam Curtis's Can't Get You Out of My Head series this year, and I enjoyed his tonal storytelling and great examples of complex moments of recent history. He does that work of connecting something that existed before modernity (e.g., racism and misogyny in China) and how it has followed through both supposedly progressive revolutions and those revolutions’ downfalls.

Geraldine Brooks did something similar for pre-modern racism in America and modern racism in her book Horse, but the best at it was Malcolm Harris in his nonficton history of Palo Alto. Also featuring horses, he finds the blueprint for contemporary Silicon Valley tech gospel so clearly precedented not only in how the same exact story of technical progress happened before (e.g., the supposedly progressive 1950s infotech boom that was actually mostly for the military), but also in how right wing it's always been (I like his chronicling of Herbert Hoover and how Stanford became the brain trust of Bush-era conservative thinking). His precise explanation of the IQ eugenics meritocracy (Stanford is in the name of the IQ test) is the kind of careful good insight-focused storytelling I wish we had more of.

Click here for the fourth post of 2023 Reading in Review when it’s posted and subscribe below to get email alerts for new posts. Full list of works discussed here.